By: Bradley Setzler

Re-posted from: http://juliaeconomics.com/2016/02/09/an-introduction-to-structural-econometrics-in-julia/

This tutorial is adapted from my Julia introductory lecture taught in the graduate course Practical Computing for Economists, Department of Economics, University of Chicago.

The tutorial is in 5 parts:

- Installing Julia + Juno IDE, as well as useful packages

- Defining a structural econometric challenge

- Data generation, management, and regression visualization

- Numerical simulation of optimal agent behavior under constraints

- Parallelized estimation by the Method of Simulated Moments

1. Installing Julia + Juno IDE, as well as useful packages

Perhaps the greatest obstacle to using Julia in the past has been the absence of an easy-to-install IDE. There used to be an IDE called Julia Studio which was as easy to use as the popular RStudio for R. Back then, you could install and run Julia + Julia Studio in 5mins, compared to the hours it could take to install Python and its basic packages and IDE. When Julia version 0.3.X was released, Julia Studio no longer worked, and I recommended the IJulia Notebook, which requires the installation of Python and IPython just to use Julia, so any argument that Julia is more convenient to install than Python was lost.

Now, with Julia version 0.4.X, Juno has provided an excellent IDE that comes pre-bundled with Julia for convenience, and you can install Julia + Juno IDE in 5mins. Here are some instructions to help you through the installation process:

- Go to http://julialang.org/downloads/ and look for “Julia + Juno IDE bundles“. Click to download the bundle for your system (Windows, Mac, or Linux).

- After the brief download (the entire Julia language + Juno IDE is less than 1GB), open the file and click through the installation instructions.

- Open Juno, and try to run a very simple line of code. For example, type 2+2, highlight this text, right-click, and choose the option Evaluate. A bubble should display 4 next to the line of code.

- Trouble-shooting: On my Mac running OS X Mavericks, 2+2 failed and an unhelpful error was produced. After some searching, I found that the solution was to install the Jewel package. To install Jewel from within Juno, just type Pkg.add(“Jewel”), highlight this text, and Evaluate. After this, 2+2 was successful.

- You have successfully installed Julia + Juno IDE, which includes a number of important packages already, such as DataFrames, Gadfly, and Optim. Now, you will want to run the following codes to install some other packages used in the econometric exercises below:

Pkg.update()

Pkg.add("Ipopt")

Pkg.build("Ipopt")

Pkg.add("JuMP")

Pkg.build("JuMP")

Pkg.add("GLM")

Pkg.add("KernelEstimator")

2. Defining a structural econometric challenge

To motivate our application, we consider a very simple economic model, which I have taught previously in the mathematical economics course for undergraduates at the University of Chicago. Although the model is analytically simple, the econometrics become sufficiently complicated to warrant the Method of Simulated Moments, so this serves us well as a teachable case.

Let denote consumption and

denote leisure. Consider an agent who wishes to maximize Cobb-Douglas utility over consumption and leisure, that is,

.

where is the relative preference for consumption. The budget constraint is given by,

,

where is the wage observed in the data,

is other income that is not observed in the data, and

is the tax rate.

The agent’s problem is to maximize subject to the budget constraint. We assume that non-labor income is uncorrelated with the wage offer, so that

. Although this assumption is a bit unrealistic, as we expect high-wage agents to also tend to have higher non-labor income, it helps keep the example simple. The model is also a bit contrived in that we treat the tax rate as unobservable, but this only makes our job more difficult.

The goal of the econometrician is to identify the model parameters and

from the data

and the assumed structure. In particular, the econometrician is interested in the policy-relevant parameter

, where,

,

and denotes the demand for consumption.

is the marginal propensity for an agent with wage

to consume in response to the tax rate.

is the population average marginal propensity to consume in response to the tax rate. Of course, we can solve the model analytically to find that

and

, where

is the average wage, but we will show that the numerical methods achieve the correct answer even when we cannot solve the model.

3. Data generation, management, and regression visualization

The replication code for this section is available here.

To generate data that follows the above model, we first solve analytically for the demand functions for consumption and leisure. In particular, they are,

Thus, we need only draw values of and

, as well as choose parameter values for

and

, in order to generate the values of

and

that agents in this model would choose. We implement this in Julia as follows:

####### Set Simulation Parameters ######### srand(123) # set the seed to ensure reproducibility N = 1000 # set number of agents in economy gamma = .5 # set Cobb-Douglas relative preference for consumption tau = .2 # set tax rate ####### Draw Income Data and Optimal Consumption and Leisure ######### epsilon = randn(N) # draw unobserved non-labor income wage = 10+randn(N) # draw observed wage consump = gamma*(1-tau)*wage + gamma*epsilon # Cobb-Douglas demand for c leisure = (1.0-gamma) + ((1.0-gamma)*epsilon)./((1.0-tau)*wage) # Cobb-Douglas demand for l

This code is relatively self-explanatory. Our parameter choices are ,

,

, and

. We draw the wage to have distribution

, but this is arbitrary.

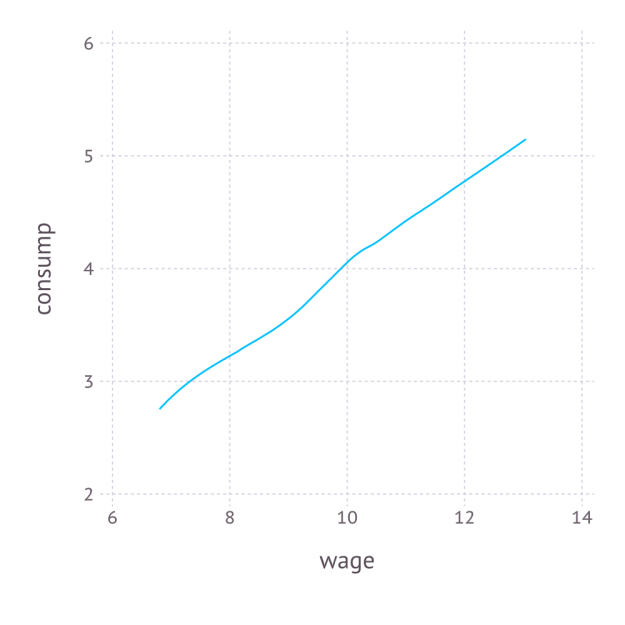

We combine the variables into a DataFrame, and export the data as a CSV file. In order to better understand the data, we also non-parametrically regress on

, and plot the result with Gadfly. The Julia code is as follows:

####### Organize, Describe, and Export Data #########

using DataFrames

using Gadfly

df = DataFrame(consump=consump,leisure=leisure,wage=wage,epsilon=epsilon) # create data frame

plot_c = plot(df,x=:wage,y=:consump,Geom.smooth(method=:loess)) # plot E[consump|wage] using Gadfly

draw(SVG("plot_c.svg", 4inch, 4inch), plot_c) # export plot as SVG

writetable("consump_leisure.csv",df) # export data as CSV

Again, the code is self-explanatory. The regression graph produced by the plot function is:

4. Numerical simulation of optimal agent behavior under constraints

The replication code for this section is available here.

We now use constrained numerical optimization to generate optimal consumption and leisure data without analytically solving for the demand function. We begin by importing the data and the necessary packages:

####### Prepare for Numerical Optimization #########

using DataFrames

using JuMP

using Ipopt

df = readtable("consump_leisure.csv")

N = size(df)[1]

Using the JuMP syntax for non-linear modeling, first we define an empty model associated with the Ipopt solver, and then add values of

and

values of

to the model:

m = Model(solver=IpoptSolver()) # define empty model solved by Ipopt algorithm @defVar(m, c[i=1:N] >= 0) # define positive consumption for each agent @defVar(m, 0 <= l[i=1:N] <= 1) # define leisure in [0,1] for each agent

This syntax is especially convenient, as it allows us to define vectors of parameters, each satisfying the natural inequality constraints. Next, we define the budget constraint, which also follows this convenient syntax:

@addConstraint(m, c[i=1:N] .== (1.0-t)*(1.0-l[i]).*w[i] + e[i] ) # each agent must satisfy the budget constraint

Finally, we define a scalar-valued objective function, which is the sum of each individual’s utility:

@setNLObjective(m, Max, sum{ g*log(c[i]) + (1-g)*log(l[i]) , i=1:N } ) # maximize the sum of utility across all agents

Notice that we can optimize one objective function instead of optimizing objective functions because the individual constrained maximization problems are independent across individuals, so the maximum of the sum is the sum of the maxima. Finally, we can apply the solver to this model and extract optimal consumption and leisure as follows:

status = solve(m) # run numerical optimization c_opt = getValue(c) # extract demand for c l_opt = getValue(l) # extract demand for l

To make sure it worked, we compare the consumption extracted from this numerical approach to the consumption we generated previously using the true demand functions:

cor(c_opt,array(df[:consump])) 0.9999999998435865

Thus, we consumption values produced by the numerically optimizer’s approximation to the demand for consumption are almost identical to those produced by the true demand for consumption. Putting it all together, we create a function that can solve for optimal consumption and leisure given any particular values of ,

, and

:

function hh_constrained_opt(g,t,w,e) m = Model(solver=IpoptSolver()) # define empty model solved by Ipopt algorithm

@defVar(m, c[i=1:N] >= 0) # define positive consumption for each agent

@defVar(m, 0 <= l[i=1:N] <= 1) # define leisure in [0,1] for each agent

@addConstraint(m, c[i=1:N] .== (1.0-t)*(1.0-l[i]).*w[i] + e[i] ) # each agent must satisfy the budget constraint

@setNLObjective(m, Max, sum{ g*log(c[i]) + (1-g)*log(l[i]) , i=1:N } ) # maximize the sum of utility across all agents

status = solve(m) # run numerical optimization

c_opt = getValue(c) # extract demand for c

l_opt = getValue(l) # extract demand for l

demand = DataFrame(c_opt=c_opt,l_opt=l_opt) # return demand as DataFrame

end

hh_constrained_opt(gamma,tau,array(df[:wage]),array(df[:epsilon])) # verify that it works at the true values of gamma, tau, and epsilon

5. Parallelized estimation by the Method of Simulated Moments

The replication codes for this section are available here.

We saw in the previous section that, for a given set of model parameters and

and a given draw of

for each

, we have enough information to simulation

and

, for each

. Denote these simulated values by

and

. With these, we can define the moments,

which is equal to zero under the model assumptions. A method of simulated moments (MSM) approach to estimate and

is then,

where is a

weighting matrix, which is only relevant when the number of moments is greater than the number of parameters, which is not true in our case, so

can be ignored and the method of simulated moments simplifies to,

Assuming we know the distribution of , we can simply draw many values of

for each

, and average the moments together across all of the draws of

. This is Monte Carlo numerical integration. In Julia, we can create this objective function with a random draw of

as follows:

function sim_moments(params) this_epsilon = randn(N) # draw random epsilon ggamma,ttau = params # extract gamma and tau from vector this_demand = hh_constrained_opt(ggamma,ttau,array(df[:wage]),this_epsilon) # obtain demand for c and l c_moment = mean( this_demand[:c_opt] ) - mean( df[:consump] ) # compute empirical moment for c l_moment = mean( this_demand[:l_opt] ) - mean( df[:leisure] ) # compute empirical moment for l [c_moment,l_moment] # return vector of moments end

In order to estimate , we need to run sim_moments(params) many times and take the unweighted average across them to achieve the expectation across

. Because each calculation is computer-intensive, it makes sense to compute the contribution of

for each draw of

on a different processor and then average across them.

Previously, I presented a convenient approach for parallelization in Julia. The idea is to initialize processors with the addprocs() function in an “outer” script, then import all of the needed data and functions to all of the different processors with the require() function applied to an “inner” script, where the needed data and functions are already managed by the inner script. This is incredibly easy and much simpler than the manual spawn-and-fetch approaches suggested by Julia’s official documentation.

In order to implement the parallelized method of simulated moments, the function hh_constrained_opt() and sim_moments() are stored in a file called est_msm_inner.jl. The following code defines the parallelized MSM and then minimizes the MSM objective using the optimize command set to use the Nelder-Mead algorithm from the Optim package:

####### Prepare for Parallelization #########

addprocs(3) # Adds 3 processors in parallel (the first is added by default)

print(nprocs()) # Now there are 4 active processors

require("est_msm_inner.jl") # This distributes functions and data to all active processors

####### Define Sum of Squared Residuals in Parallel #########

function parallel_moments(params)

params = exp(params)./(1.0+exp(params)) # rescale parameters to be in [0,1]

results = @parallel (hcat) for i=1:numReps

sim_moments(params)

end

avg_c_moment = mean(results[1,:])

avg_l_moment = mean(results[2,:])

SSR = avg_c_moment^2 + avg_l_moment^2

end

####### Minimize Sum of Squared Residuals in Parallel #########

using Optim

function MSM()

out = optimize(parallel_moments,[0.,0.],method=:nelder_mead,ftol=1e-8)

println(out) # verify convergence

exp(out.minimum)./(1.0+exp(out.minimum)) # return results in rescaled units

end

Parallelization is performed by the @parallel macro, and the results are horizontally concatenated from the various processors by the hcat command. The key tuning parameter here is numReps, which is the number of draws of to use in the Monte Carlo numerical integration. Because this example is so simple, a small number of repetitions is sufficient, while a larger number would be needed if

entered the model in a more complicated manner. The process is run as follows and requires 268 seconds to run on my Macbook Air:

numReps = 12 # set number of times to simulate epsilon gamma_MSM, tau_MSM = MSM() # Perform MSM gamma_MSM 0.49994494921381816 tau_MSM 0.19992279518894465

Finally, given the MSM estimates of and

, we define the numerical derivative,

, for some small

, as follows:

function Dconsump_Dtau(g,t,h) opt_plus_h = hh_constrained_opt(g,t+h,array(df[:wage]),array(df[:epsilon])) opt_minus_h = hh_constrained_opt(g,t-h,array(df[:wage]),array(df[:epsilon])) (mean(opt_plus_h[:c_opt]) - mean(opt_minus_h[:c_opt]))/(2*h) end barpsi_MSM = Dconsump_Dtau(gamma_MSM,tau_MSM,.1) -5.016610457903023

Thus, we estimate the policy parameter to be approximately

on average, while the true value is

, so the econometrician’s problem is successfully solved.

Bradley Setzler